Guest Author: John Sloan, University of Alabama (Birmingham)

In establishing this project, it has been my intention to encourage others to identify and expose Solutions without Problems. This report by Professor John Sloan is the first such response to that intention, and I am delighted to share it with you. Dr. Sloan has been willing to open up a topic marked by profound emotions and identify an aspect of that topic that truly qualifies as a soluprob. –Earl Babbie

Presumed Problem

Convicted sex offenders pose a major threat to communities of reoffending once released from prison.

Solution

Pass laws that require states (and the federal government) to monitor sex offenders via registration and community notification, and involuntarily commit sex offenders to psychiatric hospitals after end of sentence.

Introduction

“Public opinion reinforced by portrayals in the media and in popular culture, suggests that sex offenders will almost always repeat their predatory acts in the future and that all treatments for perpetrators are ineffective. The truth is not so cut and dried.” – Scientific American

Few crimes cause greater public outrage and concern than do so-called “sex crimes,” especially the rape or molestation of children. Many women – and more than a few men – have, themselves, been victims or have friends or relatives who have experienced sexual victimization at the hands of people they knew: priests, teachers, public officials, colleagues and supervisors at work, and family members. Women and girls experience extraordinarily high levels of sexual victimization at the hands of men and boys, many (if not most) who are known to them. Because sexual victimization has touched so many people and generated so much attention and emotion, public attitudes toward sex crime offenders tends to boil down to fear of them and extreme punitiveness toward them.

Few crimes cause greater public outrage and concern than do so-called “sex crimes,” especially the rape or molestation of children. Many women – and more than a few men – have, themselves, been victims or have friends or relatives who have experienced sexual victimization at the hands of people they knew: priests, teachers, public officials, colleagues and supervisors at work, and family members. Women and girls experience extraordinarily high levels of sexual victimization at the hands of men and boys, many (if not most) who are known to them. Because sexual victimization has touched so many people and generated so much attention and emotion, public attitudes toward sex crime offenders tends to boil down to fear of them and extreme punitiveness toward them.

In 2015, over 740,000 people in the United States were registered “sex offenders” (see Table 1) –more people than live in the Cities of San Francisco, Baltimore, or Boston. What this means is that all of these people had, since the 1990s when registration first began occurring, either served time in jail or prison or been placed on probation for a dizzying array of sex-related offenses ranging from urinating in public to violent rape of children and were, as a result, required to register with the local authorities as a sex offender.

Recent cases involving sexual misconduct by Jared Fogel (former Subway spokesperson), Jerry Sandusky (former football coach at Penn State), and actor Bill Cosby have generated a great deal of attention. At the same time, legislators have been busy proposing ever more enhanced punishments for sex offenders. Headlines such as “Alabama legislator wants to castrate sex offenders who abuse kids” or “Guam passes legislation to chemically castrate sex offenders” grab our attention and show a widely held orientation toward dealing with sex offenders. Other headlines such as “When predators are women” and “MANHUNT: Convicted sex offender allegedly lured 14-year-old girl from home” both titillate and terrify readers.

Recent cases involving sexual misconduct by Jared Fogel (former Subway spokesperson), Jerry Sandusky (former football coach at Penn State), and actor Bill Cosby have generated a great deal of attention. At the same time, legislators have been busy proposing ever more enhanced punishments for sex offenders. Headlines such as “Alabama legislator wants to castrate sex offenders who abuse kids” or “Guam passes legislation to chemically castrate sex offenders” grab our attention and show a widely held orientation toward dealing with sex offenders. Other headlines such as “When predators are women” and “MANHUNT: Convicted sex offender allegedly lured 14-year-old girl from home” both titillate and terrify readers.

| Table 1. Sex Offender Statistics (September, 2015) |

| Total number of registered sex offenders nationwide in the U.S. |

747,408 |

| Percent of sentence actually served (on average) by sex offenders |

44 |

| Percent of boys sexually molested by someone they knew |

93 |

| Percent of girls sexually molested by someone they knew |

80 |

| Percent of children sexually abused who become abusers later in life |

30 |

| Percent of sexual assaults that occur between 6:00 pm and 12:00 am |

43 |

| Source: Statistics Brain

|

Clearly, the sexual abuse of another person – adult or child – is a serious crime warranting serious punishment. However, when it comes to these types of offenses, the public and policy makers have worked hard to create a solution for a problem that does not exist.

The Mythology of Sex Offenders in America

Consider the following:

Women and children are in great danger in American society because serious sex crimes are very prevalent and are increasing more rapidly than any other type of crime.

Practically all serious sex crimes are committed by “degenerates,” “sex fiends,” or “sexual psychopaths.”

Sexual psychopaths continue to commit serious sex crimes throughout life because they have no control over their impulses.

Sexual psychopaths can be identified with a high degree of precision even before they have committed any sex crimes.

A society which punishes sex criminals, even with severe penalties, and then releases them to prey again upon women and children is failing in its duty.

Laws should be enacted to segregate such persons, preferably before but at least after their sex crimes, and to keep them confined as irresponsible patients until their malady has been completely and permanently cured.

Since sexual psychopathy is a mental malady, the professional advice as to the diagnosis, the treatment, and the release of patients as cured should come exclusively from psychiatrists.

Do these sentiments sound familiar? That the words were written by the great American criminologist Edwin Sutherland in 1950 in a famous article titled “The Sexual Psychopath Laws” should give all of us pause. What should also give us pause is what Sutherland writes next: “All of these propositions, which are implicit in the laws and explicit in the popular literature, are either false or questionable (emphasis added)” (Sutherland, 1950, p. 543). When it comes to sex offenders, indeed, “everything old is new again.” A number of scholars, including Marcus Galeste and his colleagues, have examined – and debunked – various myths about sex offenders that are often presented, repeated, and perpetuated by media, law enforcement, and state legislators. These myths, in turn, have strongly influenced policy responses to sex offenders.

One of the biggest myths about sex offenders that led directly to policies like offender registration lists and community notification requirements is that sex offenders have very high rates of recidivism. The empirical evidence, however, says otherwise. For example, Matthew R. Durose, Patrick A. Langan, Erica L. Schmitt of the U.S. Department of Justice’s Bureau of Justice Statistics published a report in 2003 that tracked patterns of rearrest, reconviction, and reimprisonment of 9,691 male sex offenders, or two-thirds of all male sex offenders released from prisons in 15 states in 1994, including 3,115 rapists, 6,576 sexual assaulters, 4,295 child molesters, and 443 statutory rapists tracked for 3 years after their release. Compared to non-sex offenders, sex offenders had a lower overall re-arrest rate. When rearrests for any type of crime (not just sex crimes) were counted, the study found that 43% (4,163 of 9,691) of the 9,691 released sex offenders were rearrested but 68% of the remaining offenders (179,391 of 262,420) were rearrested. Among sex offenders, just 3.5% were reconvicted of a sex crime within three years of being released from prison. R. Carl Hanson and Kelly E. Morton-Bourgon (2009) conducted a meta-analysis of the results of 110 published and unpublished studies of sex offender recidivism covering the period 1972 through 2008, that included 118 unique samples containing 45,398 offenders from 16 countries. Their study included three outcome measures: (a) any sexual recidivism vs. no recidivism or only nonsexual recidivism; (b) any sexual or violent recidivism vs. no recidivism or only nonviolent recidivism; and (c) any recidivism vs. no recidivism. They found that the sexual recidivism rate was 11.5%, the sexual or violent recidivism rate was 19.5%, and the general (any) recidivism rate was 33.2% over an average follow-up period of 70 months

A second myth about sex offenders is that treatment – however defined – doesn’t work (or, more strongly, “nothing works” with these offenders). Mass media, including police procedurals on TV like Law & Order SVU and news outlets, commonly portray sex offenders as being incapable of benefitting from any form of rehabilitation and therefore solutions such as chemical or actual castration, or locking offenders away for life in prison or a psychiatric hospital are the only viable solutions. Evidence however, shows a different story. Several studies have demonstrated that cognitive-behavioral therapy and multisystemic treatment can be successful in reducing recidivism by sex offenders.

A third commonly believed myth about sex offenders is that most victims fall prey to strangers, thus the popular mantra “Stranger Danger.” Again, the empirical evidence shows otherwise: most victims of rape, sexual assault, child molestation and many other sex offenses know their offenders. In one study, 3 out of 4 molested children were victimized by people they knew. According to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), in 2012 among female rape victims, perpetrators were reported to be intimate partners (51.1%), family members (12.5%), or acquaintances (40.8%) (these figure exceed 100% because respondents may have experienced more than one victimization by offenders falling into two or more categories).

Homogeneity is a fourth commonly held belief about sex offenders. That is, “all sex offenders are the same” and as a result many of the responses to them take a “one size fits all” approach. The reality is that sex offenders vary greatly in the causes of their behavior, in the types of crimes they commit, in the length of their careers, and whom they victimize. One size fits all may work for items like gloves, but not sex offender programs.

Sex Offenders Across Historical Eras

History can often prove useful for understanding how solutions to non-existent problems develop. Derek Logue (2012) has identified four historical eras that shaped government responses to sex offenders. The first era is what he calls the Construction/ Progressive Era (1880-1935), during which advances in sociology and psychology created the first stereotypes of sex offenders. The Sexual Psychopath Era (1930-1955) was important because during this period early national media sensationalized child abduction and murder cases, including the Lindbergh baby case and the Leopold and Loeb child murder case, which created public perception of an “epidemic” of these kind of cases occurring and gave rise to new laws including castration of sex offenders, involuntary civil commitment, and the first attempts at creating registries for offenders. This period also saw the FBI, under J. Edgar Hoover, make sex crimes a national focus and spread the “Stranger Danger” refrain that remains popular today. This period also saw J. Paul DeRiver establish the nation’s first “Sex Offender Bureau” in 1937 and create casebooks used to train law enforcement that emphasized sex offenders as “monsters.” Finally, this second era, marked by waves of predator panic, saw the rise of psychiatric influences on policy-making concerning sex offenders. The Rehabilitative/ Liberal Era (1950-1980) was marked by experimentation with sex offender policies, by dialogue outside the dominant “monster” view of sex offenders, distrust of law enforcement and psychiatry, and a growing social acceptance of certain “deviant” sexual behaviors. The final era, what Logue calls the Containment Era (1980-Present) has been marked by unparalleled punitive responses to sex crimes, the rebirth of old ideas about sex offenders while implementing newer, more novel ideas.

Despite differences within the four eras, Logue (2012) argues that depictions of sex offenders as “monsters” is a consistent theme and that various stereotypes of them – rather than empirical evidence – shaped legislative responses to them across the four eras.

Policies Targeting Sex Offenders

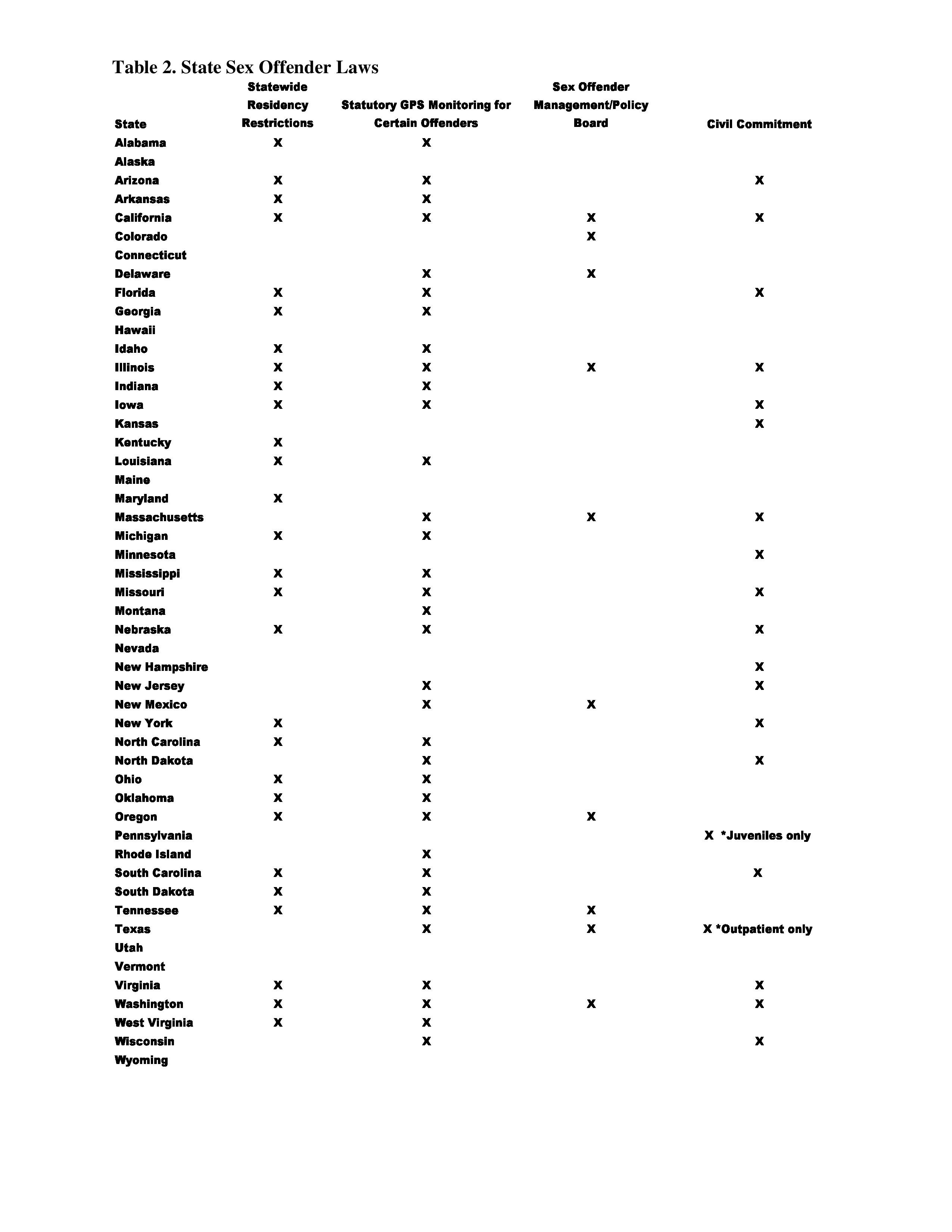

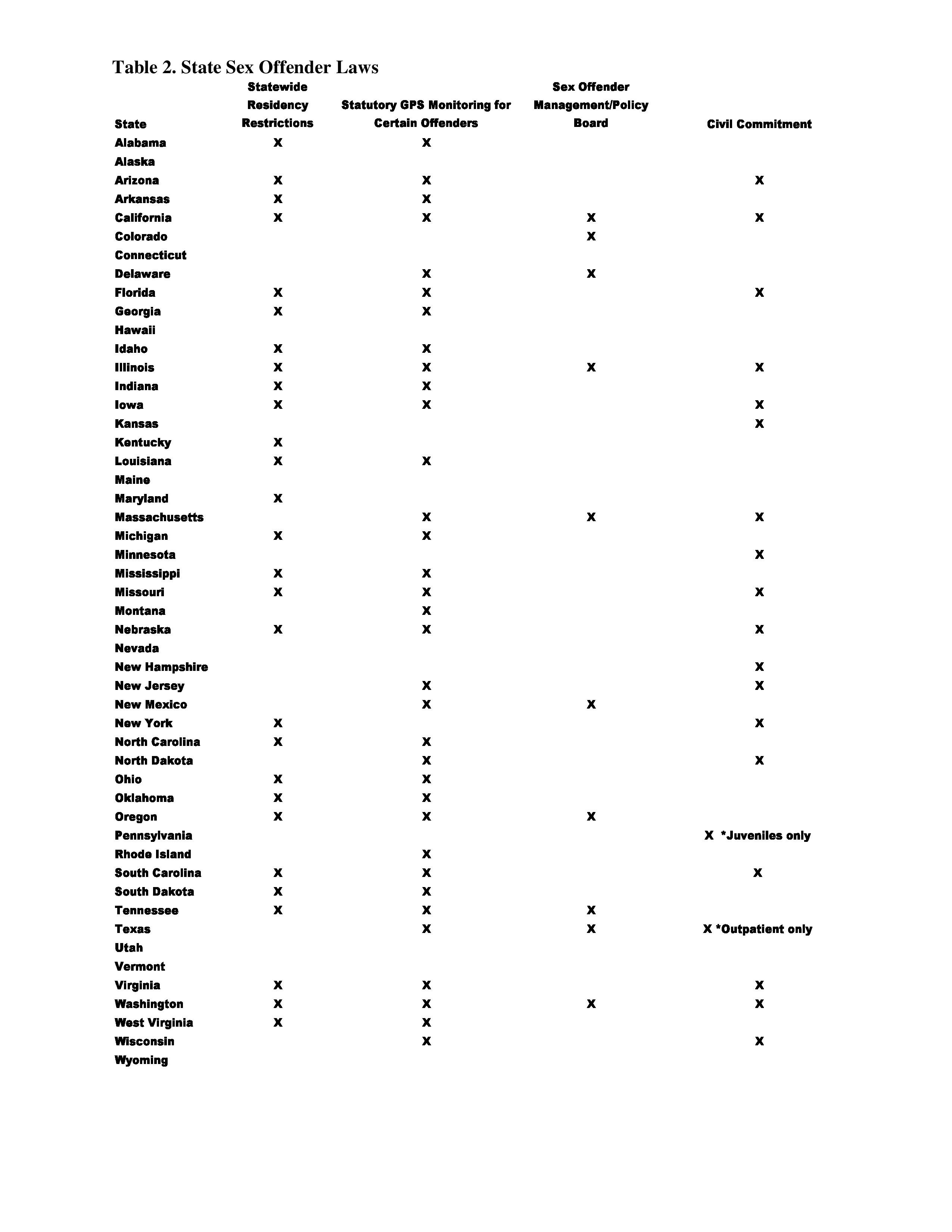

Faced with public pressure to “do something” about the perceived epidemic of sex offenders molesting innocent children, policy makers responded by creating laws requiring (1) sex offenders to register their addresses with local authorities, (2) local authorities to notify the community that a sex offender had taken up residence, and (3) commitment to psychiatric hospitals for sex offenders deemed “too dangerous” to be released back into the community. Table 2 presents a state-by-state list of policies relating to sex offenders.

Table 2. State Sex Offender Laws

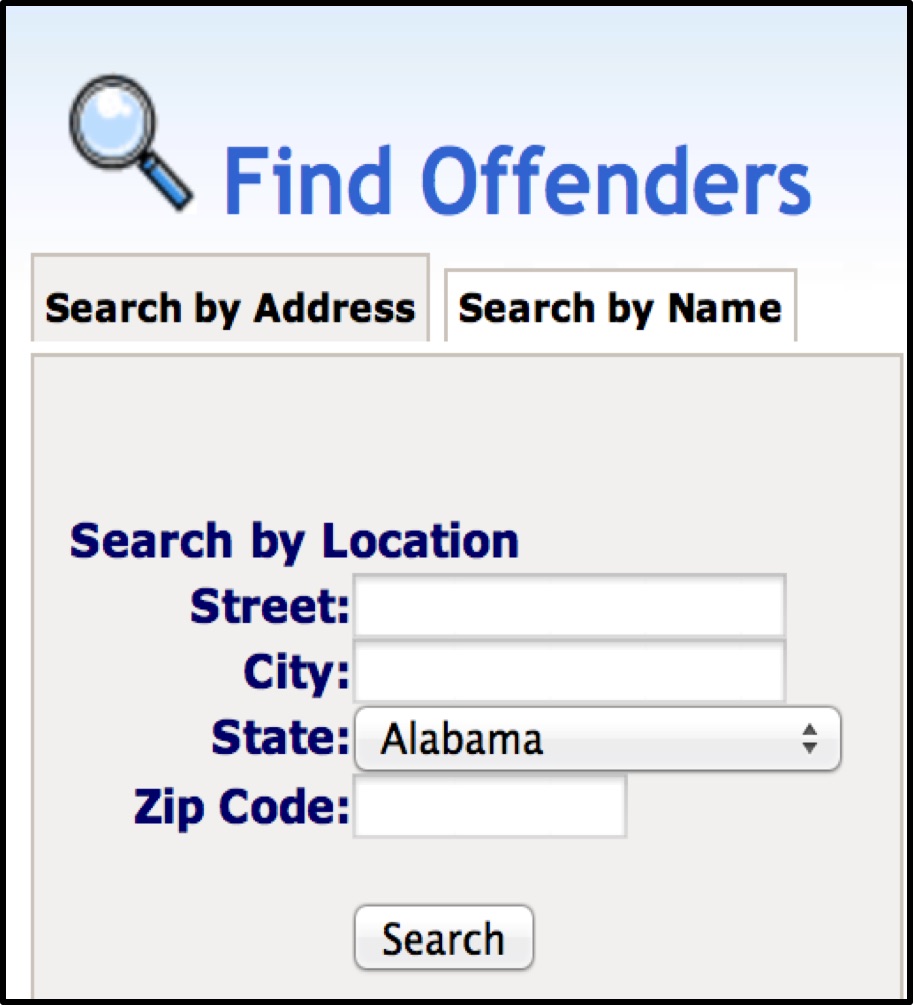

Registration and notification. Registries of sex offenders exist at the federal and state level. Their purpose is to assemble information about people deemed “sex offenders” who are required to register by law based  on their conviction offense. This information is then made available for consumption by both the public and law enforcement. Currently, all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the federal government maintain registries that are open to the public and can be searched via web portals; in some states, certain information about offenders is only available to law enforcement. In these cases, a trial judge is typically barred from considering mitigating factors with respect to registration requirements. Importantly, requirements for who must register as a “sex offender” vary greatly from one jurisdiction to another. The length of time which the offender is required to maintain his or her registration also varies by offense and jurisdiction. In some instances, offenders may be required to maintain their registration for life.

on their conviction offense. This information is then made available for consumption by both the public and law enforcement. Currently, all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the federal government maintain registries that are open to the public and can be searched via web portals; in some states, certain information about offenders is only available to law enforcement. In these cases, a trial judge is typically barred from considering mitigating factors with respect to registration requirements. Importantly, requirements for who must register as a “sex offender” vary greatly from one jurisdiction to another. The length of time which the offender is required to maintain his or her registration also varies by offense and jurisdiction. In some instances, offenders may be required to maintain their registration for life.

Registration typically involves the offender sharing with law enforcement their full name and any aliases, their current address, place of employment, telephone number(s), and email address(es). Offenders are typically photographed and fingerprinted by law enforcement, and in some cases DNA information is collected and stored. Additionally, thirty states subject registrants to restrictions that prohibit them from living or working within a defined distance of a school, public parks, and other “common areas” of the community where children may gather.

Mandatory registration of sex offenders came about because of three laws. The Jacob Wetterling Crimes Against Children and Sexually Violent Offender Registration Act of 1994 was enacted as a part of the Omnibus Crime Bill of 1994 and established guidelines for states to track sex offenders by confirming their residence annually for 10 years after release into the community or quarterly for the rest of their lives if the offender had been convicted of a violent crime like rape.

“Megan’s Law” refers to the requirement that all states and the federal government notify communities that sex offenders are living in them. The law is named after 7-year-old Megan Kanka, a New Jersey native who was brutally raped and murdered in 1994 by a convicted sex offender who was a neighbor. Since few states required registration prior to her death, the law refers to an amendment to the Jacob Wetterling Act that requires both registration and community notification of sex offenders.

The Adam Walsh Child Protection and Safety Act of 2006 is a federal statute that organized sex offenders into three tiers according to the crime committed. The law mandates that certain offenders (Tier 3 offenders) update their whereabouts every three months with lifetime registration requirements. Tier 2 offenders must update their whereabouts every six months for 25 years, and Tier 1 offenders must update their whereabouts every year for 15 years. The law makes failing to register a federal offense. States are required to publicly disclose information of Tier 2 and Tier 3 offenders, at minimum. It also contains civil commitment provisions for sexually dangerous people. The Act created a standard for sex offender registries whereby each state and territory applies identical criteria for posting offender data to their registries. Empirical evaluations of sex offender registration, such as that completed by the Government Accountability Office (GAO) in 2013, indicate that registration creates more work for law enforcement, may lead to retaliation against offenders by members of the larger community, and negatively affects housing and employment opportunities. There is also no evidence that registration has a significant effect on recidivism.

Rachel Bandy (2011) evaluated the claim that sex offender notification is positively correlated with the public’s adoption of protective behavior; this study found no statistically significant relationship between receiving  notification about a high-risk sex offender and the adoption of self-protective behaviors, controlling for differences in sociodemographics and neighborhood type. Her results undermine basic assumptions on which registration and notification have been built. Her results also indicate that notification does not support the claim the public is safer from sex offenders as a result of notification laws.

notification about a high-risk sex offender and the adoption of self-protective behaviors, controlling for differences in sociodemographics and neighborhood type. Her results undermine basic assumptions on which registration and notification have been built. Her results also indicate that notification does not support the claim the public is safer from sex offenders as a result of notification laws.

Civil commitment after end of sentence (EOS). Twenty-one states and the federal government currently allow civil commitment for sex offenders after they have completed their term of sentence. What these schemes allow is for the state to petition the court to commit the offender to a psychiatric hospital for an indefinite term because the offender poses a significant threat of reoffending. In 2010, in the landmark case United States v Comstock (560 U.S. 126), the U.S. Supreme Court upheld these schemes as constitutional.

These schemes have generally survived constitutional scrutiny on the grounds they are not a second prison sentence, but rather serve the non-criminal ends of protecting society and helping rehabilitate violent sex offenders. Legislation underlying these schemes often confirms the treatment objective by explicating statutory guidelines for sex offender treatment programs.

However, Jeslyn Miller has argued that while treatment is guaranteed by various statutes, legislation, case law, and the Constitution, the guarantee of treatment is an empty promise. Offender participation in post-incarceration treatment, in fact, harms him or her because he or she must discuss his or her fantasies and past behavior as part of the treatment plan. Prosecutors in turn can then use this information to secure further confinement. This “treatment paradox” may result in offenders electing not to seek treatment and effectively denies them “the opportunity to heal and obtain release from commitment through treatment.” Christina Mancini and Daniel Mears have likewise observed that various appeals courts have repeatedly upheld policies relating to sex offenders, despite scientific evidence calling them into question.

Is the Problem Real?

Recall that sex offender registration and notification and civil commitment after EOS are intended to prevent “monsters” from further victimizing members of the community. The question is whether the problem of sex offenders recidivating warrants the policies that have been put into place by both the federal government and the states.

Clearly, most people would agree that some sex offenders – recidivist pedophiles or rapists come to mind – are dangerous, deserve significant punishment, and probably should be monitored closely. However, among the 700,000+ registered sex offenders, how many of them fit into those particular categories? Likely very few since career pedophiles and rapists typically end up incarcerated for life.

The problem is that over the past 30 years or so, we’ve literally lumped  ALL sex offenders together and our policies treat them the same. For example, we more or less treat the 17-year-old high school student who “sexts” a nude picture of himself or an erotic message to his 16-year-old girlfriend (or vice-versa) or the young woman who urinates in public after a “night on the town” the same as someone who exposed himself to a group of school children while masturbating or sexually assaulted a woman while at a party. In the case of sexting, some overzealous prosecutors have even pursued child pornography charges against the person sending the nude image(s). In most states, all of these folks would end up on a sex offender registry and the community would receive notification these people are living there.

ALL sex offenders together and our policies treat them the same. For example, we more or less treat the 17-year-old high school student who “sexts” a nude picture of himself or an erotic message to his 16-year-old girlfriend (or vice-versa) or the young woman who urinates in public after a “night on the town” the same as someone who exposed himself to a group of school children while masturbating or sexually assaulted a woman while at a party. In the case of sexting, some overzealous prosecutors have even pursued child pornography charges against the person sending the nude image(s). In most states, all of these folks would end up on a sex offender registry and the community would receive notification these people are living there.

Who’s On Sex Offender Registries?

While one may think this would be an easy question to answer, the truth is it’s not. According to Arlissa Ackerman and her colleagues (2011), “. . . limited research has been done to shed light on the characteristics of registered sex offenders, such as their demographics, the types of offenses they have committed, their victim preferences, and the risk they may pose for future criminal behavior.” They continue by arguing that “Such analyses have been complicated by the decentralized nature of publicly available registry data and the general lack of availability of these data to researchers” despite the recent creation of a national sex offender registry. In fact, according to Ackerman and colleagues (2011) “no national database exists by which researchers can draw data from multiple states. Therefore, the few studies that have included descriptive data of samples from registered sex offenders have been conducted in individual states, and there is no standardization or uniformity to the types of characteristics described in various studies.”

One large-scale attempt to answer the above question was undertaken by Alissa Ackerman and her colleagues (2011) when they created a national profile of the registered sex offender (RSO) population, drawn from an analysis of data on 445,127 RSOs obtained from the public registries of 49 states (Michigan was not included for various technical reasons), Washington, DC, Puerto Rico and Guam between July and December of 2010. While these data are somewhat dated and there are many limitations with them (acknowledged by Ackerman and her colleagues), we have not found any similar published studies using national-level RSO data.

Below, is a summary table of their results:

Table 3. National Snapshot of Registered Sex Offenders (RSOs) (2010)

| Age (mean) |

45 |

| Age (median) |

44 |

| Age Range |

12-99 |

| % white |

66 |

| % male |

98 |

| % with victims < 14 |

70 |

| % designated as high risk or Sexually Violent Predators (SVPs) (number of states reporting)a |

13

(25) |

| % designated specifically as absconded |

5 |

| % specifically designated as homeless/transient (number of states reporting) |

6

(43) |

| % specifically designated as living in community (not reported as deceased, deported, or institutionalized) |

88% |

a Percentage does not include those listed as sexually violent or sexually dangerous. When those individuals are accounted for, the summary of those designated as SVP changed slightly to 14%.

Ackerman and her colleagues discussed their results as follows (emphasis added):

- Substantial differences in state registry variables produced challenges in developing standardized measures by which to conduct data analyses. These limitations are instructive to understanding the significant operational and definitional challenges facing the nation’s Sex Offender Registry Notification (SORN) systems, which are particularly germane to current policy deliberations occurring at national, state, and tribal jurisdictional levels concerning the future of registration and notification policy and practice.

- The sample of sex offenders in this study comprised only those contained on publicly accessible state registries; offenders not subject to public disclosure (approximately 37% of the nation’s registered sex offenders) are ostensibly rated as lower risk and therefore the current sample reflects a higher risk group (emphasis added)

- Registered sex offenders are overwhelmingly male and white although African Americans are overrepresented (22%) based on their share of the population (~13%) and are especially overrepresented in several states.

- Individuals of all ages are found on the nation’s registries, but the average RSO is in his mid-forties. This is noteworthy, because as more people are placed on registries for long durations (or life) with little attrition, the mean age will continue to grow older and include a growing proportion of aging or elderly individuals who probably pose lower risk for reoffending (emphasis added)

- Considerable numbers of RSOs do not reside in the community (emphasis added). Public Internet-based registries were designed to alert citizens to the presence of sex offenders living nearby so that action can be taken to potentially prevent victimization. It is unclear why deported or deceased offenders remain on public registries, as the public safety value of this information seems dubious

- Despite reports that over 100,000 sex offenders are missing or noncompliant, the public registries analyzed in this study provide little direct evidence to support this assertion

- Approximately 37% of RSOs are not on public registries which means over one-third of the nation’s sex offenders have been assessed by their state’s sex offender management procedure as posing a low risk for future offending. Even among those found on public registries, a wide distribution of risk exists, with a minority designated in most states as high risk, predator, or sexually violent

Among their conclusions (emphasis added):

- Painting a national picture of RSOs remains elusive and is confounded by the fragmented nature of the nation’s sex offender registry system

- The rules seeking to impose jurisdictional uniformity are far more likely to obscure important differences among registered offenders than to shed more light on them

- The considerable obstacles encountered reflect fundamental structural issues that potentially may be exacerbated rather than ameliorated by the rules

- We found considerable heterogeneity in the RSO population across multiple dimensions, contrasting the stereotypical views of sex offenders that permeate public perception. Offense titles as defined by the Adam Walsh Act are insufficient to determine an individual’s relative threat to a community or to adequately inform law enforcement officers responsible for supervision and monitoring.

Discussion

Where does all this leave us? Rejecting out-of-hand the emotional and physical scars left by sex offenders on their victims cannot – nor should it – be ignored, shrugged off, or lessened. Clearly, children and adults who experience sexual victimizations are scarred, sometimes for life. At the same time, the issue is whether current solutions address real problems associated with sex offenders, specifically with their recidivism. Does registering sex offenders reduce future offending and make communities safer? Does community notification affect steps taken by prospective victims to reduce the likelihood of victimization? Does civil commitment post EOS really incapacitate those most deserving?

When one gets past the stereotypes and the emotion, policies relating to sex offenders have created solutions for a problem that does not exist. First, there are a host of problems with registries created to track sex offenders. About one-third of offenders are not even included in publicly available registries. Registries fail to adequately differentiate among offenders’ risk for reoffending. Rules put into place in an effort to standardize registry information have seemingly made the situation worse.

Second, there is little empirical evidence indicating that sex offenders recidivate at a rate that warrants the kind of monitoring they receive. While consensus does not exist among researchers, there is reasonable evidence showing that sex offenders reoffend at levels that are often lower than non-sex offenders and do not necessarily commit another sex crime. A related aspect here is wide variability in the accuracy of predictive tools to assess sex offenders risk for recidivism. For example, a recent national-level study of high risk offenders found systematic variability in the rate of sexual recidivism based on structured risk assessment instruments. By itself, being classified as “high risk” for recidivism could not generate with any confidence the particular probability of repeat sexual offending by any one offender.

Third, and people rarely want to discuss this, are the problems created from being labeled a “sex offender” including difficulties in finding housing or employment, difficulties in developing and keeping relationships with other people, barriers to parenting (e.g., attending school-sponsored events), and backlash from neighbors. According to Frenzel and colleagues (2012) “Sex offenders, unlike other offenders, are not only punished by the sentencing sanction, but also by the stigmatization of the public registration process and community members’ knowledge of them being on the registry. As previous research has found, community notification and registration efforts have created collateral consequences for registrants as well as their families.”

Finally, there’s also an issue of fairness as well. Is it fair that our 17-year-old “sexter” should be forced to register annually for upwards of 10 years while career burglars who likely pose a much greater danger to the community once released from prison are “free” to live out their lives with far less interference from the state?

Conclusion

Sex offenders are stereotypically viewed as “monsters” from whom the state is obligated to protect its citizens. As a result, policies deemed a solution to the problem of sex offenders have been freely adopted by all levels of government despite scientific evidence indicating that the theories upon which they are based are flawed and specific policies like registration, notification, and civil commitment have unintended and gravely negative consequences for offenders that may actually cause them to engage in further criminality.

© Earl Babbie 2016, all rights reserved Terms of Service/Privacy

Further Reading

Garland, D. (2002). The culture of control. Chicago: University of Chicago Press.

Jenkins, P. (1998). Moral panic: Changing concepts of the child molester in modern America. New Haven, Ct: Yale University Press.

Leon, C. (2011). Sex fiends, perverts, and pedophiles: Understanding sex crime policy in America. New York: New York University Press.

Zilney, L. & Zilney, L. (2009). Perverts and predators. Lanham, MD: Rowman & Littlefield Publishing Group.

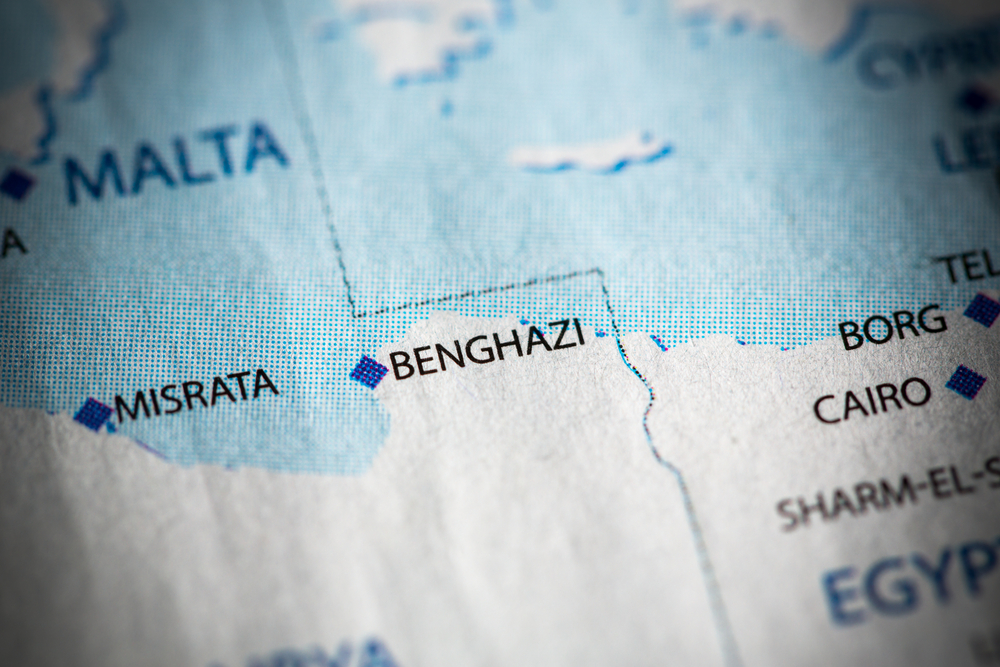

Cairo came under attack by a mob protesting an anti-Muslim film produced earlier in California. While the Cairo attack was underway, another mob attacked the American consulate in Benghazi, Libya. Four Americans, including Ambassador Chris Stevens, were killed in the latter attack.

Cairo came under attack by a mob protesting an anti-Muslim film produced earlier in California. While the Cairo attack was underway, another mob attacked the American consulate in Benghazi, Libya. Four Americans, including Ambassador Chris Stevens, were killed in the latter attack.Marine compound, killing two hundred and forty-one servicemen. The U.S. military command, which regarded the Marines’ presence as a non-combative, “peace-keeping mission,” had left a vehicle gate wide open, and ordered the sentries to keep their weapons unloaded. The only real resistance the suicide bomber had encountered was a scrim of concertina wire. When I arrived on the scene a short while later to report on it for the Wall Street Journal, the Marine barracks were flattened. From beneath the dusty, smoking slabs of collapsed concrete, piteous American voices could be heard, begging for help. Thirteen more American servicemen later died from injuries, making it the single deadliest attack on American Marines since the Battle of Iwo Jima.

attack was still underway, it was assumed that it was another reaction to the anti-Islam film, which provoked the Cairo embassy attack. As time went on and more information surfaced, it appeared that the Benghazi was independently planned and unrelated to the film. In the process of discovery, mixed reports were issued by the administration, producing some initial confusion among the public.

attack was still underway, it was assumed that it was another reaction to the anti-Islam film, which provoked the Cairo embassy attack. As time went on and more information surfaced, it appeared that the Benghazi was independently planned and unrelated to the film. In the process of discovery, mixed reports were issued by the administration, producing some initial confusion among the public. effort to tailor reports of the attack so as to avoid any responsibility by the President or his Secretary of State. Other charges indicated that Secretary Clinton had either purposely or ineptly failed to protect the embassy and mismanaged the response to the attack once it began. More radical critics even alleged Secretary Clinton knew about the attack in advance but kept it secret from the embassy staff–and when the Air Force wanted to help, she told them not to do so.

effort to tailor reports of the attack so as to avoid any responsibility by the President or his Secretary of State. Other charges indicated that Secretary Clinton had either purposely or ineptly failed to protect the embassy and mismanaged the response to the attack once it began. More radical critics even alleged Secretary Clinton knew about the attack in advance but kept it secret from the embassy staff–and when the Air Force wanted to help, she told them not to do so.Carolina, said his committee exists because the focus of the previous seven committees that investigated the attacks were “narrow in scope.” He said that his committee’s investigations are more comprehensive, including plans to interview a total of 70 people and review 50,000 “new” documents. New documents include nearly 8,000 emails sent by Ambassador Chris Stevens, whom Gowdy called a “prolific emailer.”

funding; in 2012, they cut another $331 million. [Darrell] Issa once personally voted to cut almost 300 diplomatic security positions. In 2011, after one of many fruitless trips to the Hill to beg House Republicans for resources, an exhausted, prophetic Hillary Clinton warned that cuts to embassy spending “will be detrimental to America’s national security.”

succeed John Boehner as Speaker of the House, publicly announced the real problem the investigations were intended to solve. Challenged by a conservative interviewer to name anything the Congress had achieved, McCarthy replied:

succeed John Boehner as Speaker of the House, publicly announced the real problem the investigations were intended to solve. Challenged by a conservative interviewer to name anything the Congress had achieved, McCarthy replied:Benghazi special committee, a select committee. What are her numbers today? Her numbers are dropping. Why? Because she’s un-trustable. But no one would have known any of that had happened had we not fought and made that happen.

Few crimes cause greater public outrage and concern than do so-called “sex crimes,” especially the rape or molestation of

Few crimes cause greater public outrage and concern than do so-called “sex crimes,” especially the rape or molestation of  Recent cases involving sexual misconduct by

Recent cases involving sexual misconduct by

on their conviction offense. This information is then made available for consumption by both the public and law enforcement. Currently, all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the federal government maintain registries that are open to the public and can be searched via web portals; in some states, certain information about offenders is only available to law enforcement. In these cases, a trial judge is typically barred from considering mitigating factors with respect to registration requirements. Importantly, requirements for who must register as a “sex offender” vary greatly from one jurisdiction to another. The length of time which the offender is required to maintain his or her registration also varies by offense and jurisdiction. In some instances, offenders may be required to maintain their registration for life.

on their conviction offense. This information is then made available for consumption by both the public and law enforcement. Currently, all 50 states, the District of Columbia, and the federal government maintain registries that are open to the public and can be searched via web portals; in some states, certain information about offenders is only available to law enforcement. In these cases, a trial judge is typically barred from considering mitigating factors with respect to registration requirements. Importantly, requirements for who must register as a “sex offender” vary greatly from one jurisdiction to another. The length of time which the offender is required to maintain his or her registration also varies by offense and jurisdiction. In some instances, offenders may be required to maintain their registration for life. notification about a high-risk sex offender and the adoption of self-protective behaviors, controlling for differences in sociodemographics and neighborhood type. Her results undermine basic assumptions on which registration and notification have been built. Her results also indicate that notification does not support the claim the public is safer from sex offenders as a result of notification laws.

notification about a high-risk sex offender and the adoption of self-protective behaviors, controlling for differences in sociodemographics and neighborhood type. Her results undermine basic assumptions on which registration and notification have been built. Her results also indicate that notification does not support the claim the public is safer from sex offenders as a result of notification laws.

California made the practice officially legal, though it had been informally tolerated previously unless it was done recklessly. As the LA Times Reported (2016):

California made the practice officially legal, though it had been informally tolerated previously unless it was done recklessly. As the LA Times Reported (2016):

and secular programs were popular during the second half of the 20th century and into the beginning of the 21st. In some cases. individuals voluntarily sought conversion as an escape from the stigma of being gay. And in other cases the impetus came from the parents of gays.

and secular programs were popular during the second half of the 20th century and into the beginning of the 21st. In some cases. individuals voluntarily sought conversion as an escape from the stigma of being gay. And in other cases the impetus came from the parents of gays.