Student Author

Andrew Calloway, Chapman University

NOTE: Student submissions of soluprobs are welcomed at babbie@chapman.edu

ANOTHER NOTE: I posted an earlier piece on the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution, and this student submission brings additional evidence to the discussion.

Background Narrative

After World War II, the United States was involved in a Cold War with the Soviet Union. The United States began to adopt the foreign policy of containment that was implemented throughout the 1940s-1960s. The containment policy was the effort in “trying to prevent the Soviet communism from expanding its empire.” (Rosati, Jerel A. & Scott, James M. 2014:29-32)

The containment policy was proposed in the Truman Doctrine in 1947 when containing communism in Greece and Turkey. Hodgson a political analyst described the Truman Doctrine as containing “the seeds of American of economic aid, economic or military, to more than one hundred countries; of mutual defense with more than forty of them…” (Hodgson 1976:32) Other academics believe the containment policy led to national security concerns influencing United States foreign policy for the entirety of the Cold War.

Presumed Problem

In the 1950s the United States began to worry after the creation of the People’s Republic of China and the beginning of communism in the Asian continent. This was also shown in the conflict in Korea during 1950-1953.

In February 1950, the National Security Council (NSC) passed NSC document 64 stating that Indochina was “a key area under immediate threat.” Again in 1952, the NSC passed another document on Indochina, NSC document 68. In 1954, President Eisenhower brought up the domino theory in one of his speeches, this belief was if Vietnam fell into communism, then neighboring countries in Southeast Asia will fall under communist rule as well, most particularly Laos and Cambodia. This idea brought a more militaristic approach in containing communism and increased United States involvement in Vietnam throughout the 1950s-1960s. (Kissinger, Henry 2003:13-20)

By the end of the Eisenhower administration in 1960, Eisenhower warned John F. Kennedy of the conflict of Vietnam as crucial. Eisenhower did not want the domino theory to become a reality. Under the Kennedy administration, stopping communism in Vietnam became a huge political interest, and would be considered a victory for the United States against the Soviet Union in political ideologies. According to Kissinger, by the time President Kennedy took office, there were 900 American military personnel in Vietnam, 3,164 in 1961, and almost tripled to 16,263 by 1963. (Kissinger 2003:34)

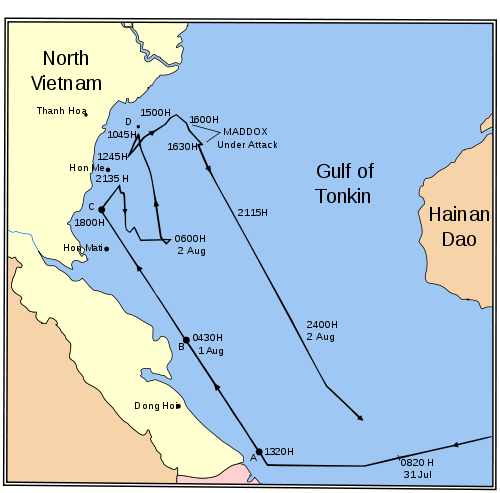

The escalation and political controversy in Vietnam began in August 1964 when news came back to the United States that North Vietnamese forces attacked the destroyer USS Maddox near the Gulf of Tonkin, this would later be called the Gulf of Tonkin incident, and led to a push for further military involvement in Vietnam by elected officials in Washington D.C. (Kissinger 2003: 35)

The escalation and political controversy in Vietnam began in August 1964 when news came back to the United States that North Vietnamese forces attacked the destroyer USS Maddox near the Gulf of Tonkin, this would later be called the Gulf of Tonkin incident, and led to a push for further military involvement in Vietnam by elected officials in Washington D.C. (Kissinger 2003: 35)

Solution to the Problem

The Gulf of Tonkin incident took place on August 2, 1964, two days later on August 4, President Johnson announced the Gulf of Tonkin Resolution and it immediately passed on August 7, giving Johnson the authority to increase U.S. involvement in Vietnam. The Tonkin Gulf resolution gave Johnson and Nixon legal basis for implementing military policies in Vietnam since the resolution was approved by the legislative branch of the U.S. government. The resolution was passed almost unanimously, the House vote was 416-0, and the Senate vote was 88-2. The two Senators who opposed the resolution were Democratic senators Wayne Morse of Oregon, and Ernest Gruening of Alaska. (Public Law 88-408, 88th Congress, August 7, 1964)

The solution to the Gulf of Tonkin incident would become a major setback for the United States in preventing communism, and a huge drop in public opinion regarding both the Vietnam War and approval of the United States government. The signing and approval from Congress expanded the powers of the Executive branch as stated in the resolution that the President as Commander in Chief should “take all necessary measures to repel any armed attack against the forces of the United States.” The next two sections of the Gulf of Tonkin resolution addresses the U. S. national interest and bringing peace and security to Southeast Asia. This later became a problem when Congress lacked sufficient knowledge of the situation and was unable to affect the military policies passed by the President later into the conflict. (Public Law 88-408, 88th Congress, August 7, 1964)

Empirical Evidence that the Problem did not exist

According to Lieutenant Commander Pat Paterson of the U.S. Navy stated that some of the information of what happened at the Gulf of Tonkin was “cloaked” and not really explained in the decision making process between the Secretary of Defense Robert McNamara and President Johnson in 1964. Recent documents of classified information being released in 2005 and 2006 have revealed many facts of what really happened in the Gulf of Tonkin incident and have helped historians reconstruct the incident.

In one of the reports by the NSA it states the second attack did not happen at the night of August 2, 1964. But by 1965 President Johnson has issued air raids and bombing campaigns under the codename Rolling Thunder, the United States began to use as much force possible to end the war quickly. This proved to not be the case as much as 500,000-600,000 American troops were committed in the Vietnam War by 1969.

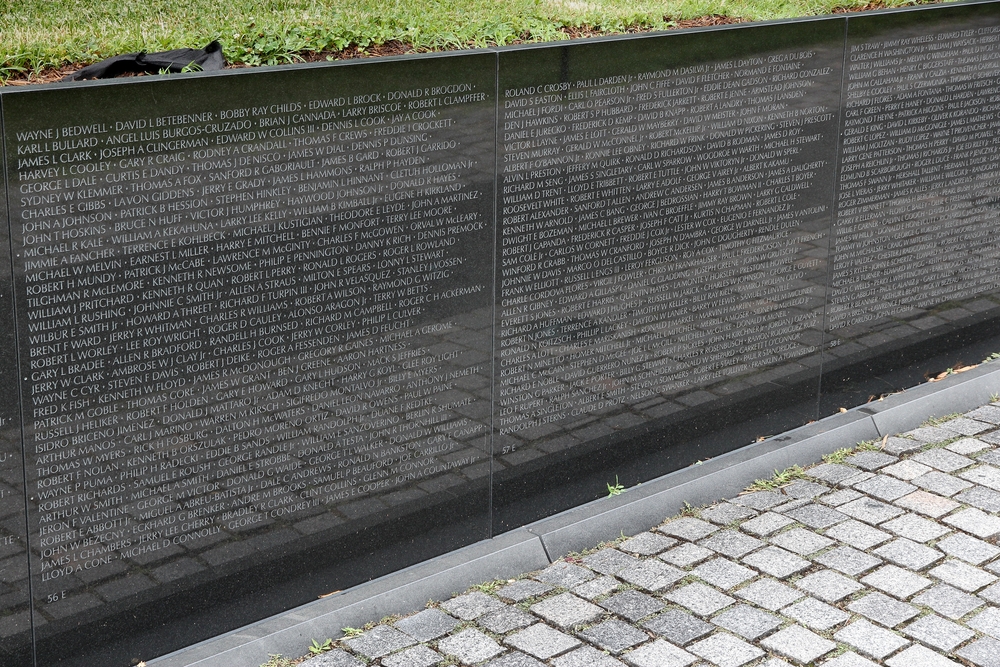

The war began to be costly as it became to be estimated as much $173 billion was spent, and about 58,220 Americans dead, and 1,643 missing. It is still a problem today with Vietnam war veterans suffering from PTSD. (Kissinger 2003: 36-38) (Naval History Magazine 2008: Volume 22 Number 1)

Consequences of the “Solution”

With the evidence provided, the Gulf of Tonkin incident and the increased involvement in the Vietnam War greatly changed the powers and policy making of the United States government. Near the end of the Vietnam War (1969-1973), public opinion towards the Vietnam War, along with the Civil Rights protests, led to a strong opposition and push for bringing American soldiers back to the United States. This led to Congress becoming more aggressive in its constitutional powers during times of war and conflict.

Congress became a more rational political actor during the Nixon administration, and began to analyze the cost and benefits of the Vietnam War as it was reaching its fourth US president being involved with the conflict. A hypothesis by Burstein, and Freudenburg stated that “Congress will respond to public opinion.” It must have been public opinion with its strong opposition that made Congress turn against the Vietnam War, and ignore the political decisions made back in 1964. (Burstein, Paul & Freudenburg, William 1978:99-122)

By 1969, the policy of “Vietnamization” was proposed by the Nixon administration, even though Nixon opposed the idea to an extent. Nixon feared the image of American troops withdrawing from Vietnam as a loss for the United States and a victory for the communist regimes. The resolution was passed and by 1973 almost all American troops had withdrawn from Vietnam, and that same year Congress passed the War Powers Resolution stating that the President should consult with Congress in regard to decisions that engage U.S. forces and military.

In conclusion, the Vietnam War did have its negative consequences in casualties and the cost of funding for almost two decades, but at the same time it did reinforce the Constitutional powers and limitations on both the legislative and executive branches. Public opinion also stepped in to have a say on the war with the peace protests, and how people began to pay more attention to the government and its decisions on the war as it was the first televised conflict, with live coverage.

The Vietnam War with its complexities changed the way the public and politicians view foreign intervention for the remainder of the Cold War and leading up to the 21st century. As quoted by General Fred C. Weyand in 1976, “When the Army is committed the American people are committed, when the American people lose their commitment it is futile to try to keep the Army committed.” (Summers, Harry G. 1995:11-15)

Bibliography

Burstein, Paul & Freudenburg, William 1978. Changing Public Policy: The Impact of Public Opinion, Antiwar Demonstrations, and War Costs on Senate Voting on Vietnam War Motions The University of Chicago Press

Kissinger, Henry 2003. Ending the Vietnam War: A History of America’s Involvement in and Extrication from the Vietnam War Simon & Schuster Inc.

Moise, Edwin E. 1996. Tonkin Gulf and the Escalation of the Vietnam War University of North Carolina Press

Paterson, Pat 2008. Naval History Magazine: The Truth About Tonkin Volume 22, Number 1, U.S. Naval Institute

Rosati, Jerel A. & Scott, James M. 2014. The Politics of United States Foreign Policy Cengage Learning Inc.

Summers, Henry G. 1995. On Strategy: A Critical Analysis of the Vietnam War Presidio Press

Tonkin Gulf Resolution; Public Law 88-408, 88th Congress, August 7, 1964. General Records of the United States Government; Record Group 11; National Archives

Administration enacted the “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy, which mandated that openly homosexual citizens were barred from enlisting while those who remained closeted were able to serve contingent that they keep their orientation private. Reasoning behind this inequitable act included undocumented perceptions on gays lacking the ability to work and interact productively with others (straight or gay) in the military. Relying on analyses from multiple scholarly journals, this paper aims to scrutinize original research prompting the policy, as well as any ramifications resulting from it. Granted while President Bill Clinton expressed the DADT as a “major step forward” from previous enlistment requirements, the corollary that followed 1994 could have been avoided if the initial presumed perceptions of homosexuals had been debunked.

Administration enacted the “Don’t Ask Don’t Tell” (DADT) policy, which mandated that openly homosexual citizens were barred from enlisting while those who remained closeted were able to serve contingent that they keep their orientation private. Reasoning behind this inequitable act included undocumented perceptions on gays lacking the ability to work and interact productively with others (straight or gay) in the military. Relying on analyses from multiple scholarly journals, this paper aims to scrutinize original research prompting the policy, as well as any ramifications resulting from it. Granted while President Bill Clinton expressed the DADT as a “major step forward” from previous enlistment requirements, the corollary that followed 1994 could have been avoided if the initial presumed perceptions of homosexuals had been debunked. Furthermore, revoking the right to be honest of one’s sexual orientation can actually foster harmful results as there are many proven benefits from disclosing this information (Kavanagh, 1995). The military had expressed concerns of “unit cohesion”, implying that heterosexuals will find difficulty integrating with open homosexuals, and may even refuse to work with them. However, one in three American adults know an uncloseted homosexual, and those with continuing relationships with gays tend to express positive attitudes towards gay people as a group (Herek, 1988). In his research, Dr. Gregory Herek also concluded that “ongoing interpersonal contact in a supportive environment where common goals are emphasized and prejudice is clearly unacceptable is likely to foster positive feelings toward gay men and lesbians.”

Furthermore, revoking the right to be honest of one’s sexual orientation can actually foster harmful results as there are many proven benefits from disclosing this information (Kavanagh, 1995). The military had expressed concerns of “unit cohesion”, implying that heterosexuals will find difficulty integrating with open homosexuals, and may even refuse to work with them. However, one in three American adults know an uncloseted homosexual, and those with continuing relationships with gays tend to express positive attitudes towards gay people as a group (Herek, 1988). In his research, Dr. Gregory Herek also concluded that “ongoing interpersonal contact in a supportive environment where common goals are emphasized and prejudice is clearly unacceptable is likely to foster positive feelings toward gay men and lesbians.” consequences than good. Externalities such as higher military costs, lower retention rates, less favorable opinions on the military, etc. all played a role in Congress’ decision to repeal the DADT in 2010.

consequences than good. Externalities such as higher military costs, lower retention rates, less favorable opinions on the military, etc. all played a role in Congress’ decision to repeal the DADT in 2010.

cites Jana Mason of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, who reported that those attempting to enter the U.S. under refugee status are the single most heavily screened and vetted category of persons. The process requires referrals and background checks by multiple government agencies, including the National Terrorism Center. In addition, Syrian refugees must go through added screening, with face-to-face interviews. All gathered information is extensively fact-checked and privately investigated. The Department of Homeland Security goes through every individual case, and approves or rejects each one accordingly.

cites Jana Mason of the United Nations High Commissioner for Refugees, who reported that those attempting to enter the U.S. under refugee status are the single most heavily screened and vetted category of persons. The process requires referrals and background checks by multiple government agencies, including the National Terrorism Center. In addition, Syrian refugees must go through added screening, with face-to-face interviews. All gathered information is extensively fact-checked and privately investigated. The Department of Homeland Security goes through every individual case, and approves or rejects each one accordingly. Such differences are important to note because recent fears of terrorist attacks in the United States have been stirred in large part by attacks that occurred in Europe. The report concludes that in the U.S., the threat of terrorist attacks by way of Syrian refugees is widely over-exaggerated because our vetting system is so thorough.

Such differences are important to note because recent fears of terrorist attacks in the United States have been stirred in large part by attacks that occurred in Europe. The report concludes that in the U.S., the threat of terrorist attacks by way of Syrian refugees is widely over-exaggerated because our vetting system is so thorough.

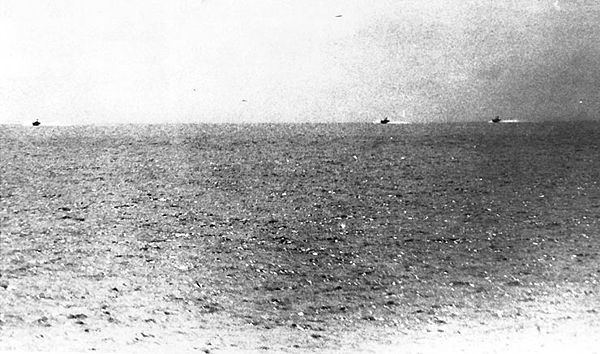

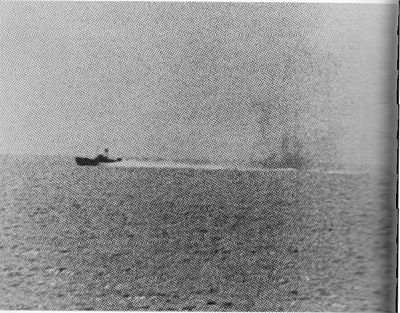

Vietnam was radically changed by the events of August 2, 1964, at the Gulf of Tonkin off the coast of North Vietnam, near the Chinese border. As reported at the time, three North Vietnamese torpedo boats from the 135th Torpedo Squadron attacked American destroyer, USS Maddox. The Maddox was unharmed, but Navy fighters claimed to have damaged the torpedo boats.

Vietnam was radically changed by the events of August 2, 1964, at the Gulf of Tonkin off the coast of North Vietnam, near the Chinese border. As reported at the time, three North Vietnamese torpedo boats from the 135th Torpedo Squadron attacked American destroyer, USS Maddox. The Maddox was unharmed, but Navy fighters claimed to have damaged the torpedo boats.